(Larry Cohen, US, 1976, 91 minutes)

"I miss the pictures that he made. I miss his spirit. And I miss the spirit of the times, which we can truly say was the renegade spirit."

--Martin Scorsese in King Cohen: The Wild World of Larry Cohen

Writer, director, and raconteur Larry Cohen, who passed away in 2019 at the age of 82, was known for his run and gun style of filmmaking. He was the kind of director who shot so quickly and efficiently that he could get around the permits necessary for filming in large urban centers, like New York City.

That's exactly how he shot 1976's God Told Me To, which incorporates real-life footage from the St. Patrick's Day parade in Manhattan and the Feast of San Gennaro in Little Italy (against Cohen's wishes, Roger Corman's New World Pictures released the film as The Demon in some markets).

In his 2003 commentary track on the new Blu-ray, Cohen tells Blue Underground CEO Bill Lustig any number of colorful stories about the making of the film (King Cohen director Steve Mitchell and horror writer Troy Howarth handle the second track).

It doesn't hurt that these two have known each other for decades, since Cohen wrote all three of Lustig's Maniac Cop movies. He also wrote Lustig's last film, 1996's Uncle Sam.

For Cohen's fifth feature, he tapped handsome, brooding Robert Forster, who had made such a vivid impression in Haskell Wexler's Medium Cool, to play the lead.

Had Forster stuck around, the film would have had an entirely different vibe, but alas, the actor couldn't stop chewing gum! Even after Cohen told him, repeatedly, to spit it out, Forster would pretend that he had--and then start chewing again. He had been warned, and so Cohen fired him.

For the record, Forster has claimed that he quit because Cohen wouldn't stop yelling at him. Nonetheless, they would reconnect in the years to come, hit it off, and work together in Cohen's final directorial effort, Original Gangstas, with Forster's Jackie Brown costar, Pam Grier. As Cohen notes, the Forster of 1996 was no longer the arrogant fellow of old.

To replace him, he found an actor even better suited for the part of a devout Catholic detective investigating a series of faith-based murders: Tony Lo Bianco, a compact fellow with a grave countenance. He had appeared, to memorable effect, in William Friedkin's The French Connection and Leonard Kastle's The Honeymoon Killers (which was partly directed by Scorsese).

Lo Bianco's origins recalled those of his contemporary, Al Pacino, another Italian-American outer-borough actor who divided his time between the stage and the screen, except Lo Bianco wouldn't hit the same heights. Early on, he got typecast as a gangster, and his subsequent career consists primarily of TV movies and low-budget crime pictures. Now 85, he possesses the same kind of stick-to-it-iveness as Pacino, since he's still working.

God Told Me To starts out like a crime procedural in the vein of early-career Friedkin or Sidney Lumet before segueing into something pulpier (notably, Lo Bianco had appeared briefly in Lumet's Serpico three years earlier).

Initially, Peter Nicholas sets out to determine why several New Yorkers, including a cop and a family man, have turned into killing machines without apparent motivation.

In each instance, they look the detective in the eye and state, "God told me to," before taking their own lives, but just exactly what God are they referring to and why would he make such a request?

Cohen opens with a sniper (A Chorus Line's Samuel Williams) on a water tower--the same water tower that appears in his 1973 Black Caesar sequel, Hell Up in Harlem. I couldn't say whether he was inspired by Charles Whitman's 1966 shooting rampage at the University of Texas, but it's the first thing that came to mind, not least because I had just watched Peter Bogdanovich's 1968 Whitman-inspired debut, Targets, a few weeks ago.

The next massacre erupts during the St. Patrick's Day parade when Andy Kaufman's cop goes on a killing spree. It would mark the future Taxi star's film debut, and he makes one hell of an impression. Cohen had caught one of the young comedian's gigs, and decided that he had to work with him.

Ironically, the audience, as Cohen remembers, had booed Kaufman's anti-comedy routine, but he loved it, accurately predicting that stardom was his for the taking. The two would stay in touch until Kaufman's death from lung cancer less than a decade later. He was only 35.

Nicholas next questions a man (Robert Drivas) who woke up, threw on a robe, and slaughtered his family. The man betrays no emotion whatsoever as he calmly answers Nicholas's questions. The detective is so unnerved that associates have to pull him off the guy lest he throttle him to death.

Any cop would be rattled by these encounters, but Nicholas has other reasons for reacting the way he does, since the investigation leads him to reconstruct his adoption history, culminating in a showdown with his birth mother (a terrific Sylvia Sidney, who had worked with Fritz Lang and Alfred Hitchcock in the 1930s) about the father he never knew. In the process, the film segues from procedural to sci-fi weirdness. Though Nicholas doesn't start out as a killer, he turns out to have something in common with the killers, and the more he learns, the more dangerous he becomes.

Not all of this plays out as effectively as it could, since Cohen loses some control over his material as the revelations accumulate--fitting, since the revelations cause his protagonist to lose control--but Lo Bianco makes for a consistently strong, compelling lead (you'd never know he was starring in a play and auditioning for parts during the shoot). Another standout: Sandy Dennis (Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?) as Nicholas's wife, a more effective foil than the comparatively anodyne Deborah Raffin as his girlfriend.

Although God Told Me To doesn't examine religious fervor--particularly the Christian variant--as rigorously as I had hoped, it confirms Cohen's frustration with those who insist on inflicting their religious beliefs on others (though he grew up in a Jewish household, I have no idea if he was observant). As Mike Kellin's Deputy Commissioner states, in words as relevant today as they were then, "People who are too goddamned religious make a lot of trouble for everybody."

Prior to God Told Me To, I had only seen one Cohen-directed film, 1982's Q: The Winged Serpent, so I set out to watch his first four features to see how they might have predicted or led to his fifth. I also watched 1985's The Stuff, because why not? Though it wasn't a hit at the time, it's one of his most purely entertaining efforts with its unflappable-kid lead, catchy jingle, and colorful commercials. The low budget shows in the primitive digital effects, but it ranks among the finest horror comedies of the 1980s, highlighted by a go-for-broke performance from the late Paul Sorvino as a militia man who saves the day--a plot development that wouldn't work quite so well in our post-millennial era of Proud Boys and Oath Keepers.

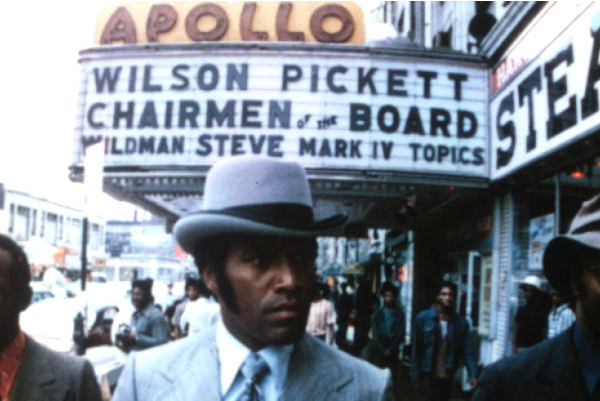

With Black Caesar and Hell Up in Harlem, both released in 1973, Cohen put his stamp on the blaxploitation genre. If former pro football player Fred "The Hammer" Williamson isn't as skilled of an actor as Lo Bianco or Sorvino, he's a bold and charismatic one who could rock the hell out of a fitted suit.

Though I wouldn't describe Larry Cohen as a misogynist, he does Bond Girl Gloria Hendry dirty in this duo, the sequel above all. There's no reason Black women should only play likable love interests, but he takes a rather sadistic approach to Helen.

Though these films were intended for the grind house circuit, it isn't hard to imagine mostly-male audiences booing whenever Helen makes an appearance--and then cheering when Williamson's Tommy sexually assaults her and then snatches her children away. Not to give too much away, but things don't end well. (I had no such qualms with the Dennis and Raffin characters in God Told Me To.) All told, though, the action is good fun and Cohen finagled some top-flight Black musicians: the immortal James Brown for Black Caesar and Edwin Starr and Fonce Mizell for Hell Up in Harlem.

Similarly, the music throughout Cohen's entire 1970s output transcends its B-movie surroundings, since Miklós Rózsa (Spellbound) scored 1977's The Private Files of J. Edgar Hoover and Bernard Herrmann (Psycho) scored 1974's It's Alive, another high point in Cohen's filmography with a sympathetic turn from John P. Ryan (Runaway Train) as a father trying to square the circle between love for his infant son, unalloyed fear, and concern that the little guy will rip the whole town to shreds if he isn't stopped.

After It's Alive, Herrmann scored Cohen-admirer Martin Scorsese's 1976 Taxi Driver. His classy, orchestral scores elevate both films considerably. Though Herrmann had agreed to score God Told Me To, he died a mere 15 hours after screening the film. BBC stalwart Frank Cordell would step in with a score that nicely recalls Herrmann's work.

Of the Cohen films I've seen, I would be hard pressed to declare God Told Me To his best--I'm also partial to Bone and It's Alive--but it's certainly a contender, thanks largely to Lo Bianco's performance and a chilling ending that I should've seen coming, but didn't. If we're meant to take it literally, Cohen concludes that God doesn't exist. Or that God is an alien (he has cited Erich von Däniken's bestseller Chariots of the Gods as an inspiration).

One way or the other, it's an enduring human impulse: to use God as an excuse to commit heinous acts. That isn't fiction, it's fact. Larry Cohen just found a fantastical way to depict the phenomenon, and yet he was enough of a realist to conclude with an explanation rather than a solution.

Much like the mutant baby in It’s Alive, the God in this film isn't indestructible, but nor is he the only one of his kind. And if there can be two Gods eager to bend mankind to their will, well, there could easily be more.

God Told Me To is available on a two-disc 4K Ultra HD + Blu-ray through Blue Underground. It’s available to stream through several digital play operators including Apple TV, Google Play, Vudu, and YouTube.

Images: New World Pictures / Horror Geek Life (Tony Lo Bianco), Film Affinity (Demon poster), The Criterion Collection (Lo Bianco and Shirley Stoler in The Honeymoon Killers), DVD Beaver (Sandy Dennis), Harlem World Magazine (Fred Williamson), and Horror Obsessive (Lo Bianco).