Friday, August 31, 2007

JLG 101: The Girl and a Gun of Pierrot le Fou

(Jean-Luc Godard, France/Italy, 1965, 35mm, 110 mins)

Marianne: Pierrot le Fou!!!

Ferdinard: My name is Ferdinard. I have told you often enough. Christ almighty!

***** ***** ***** ***** ***** ***** ***** ***** ***** *****

Like Wong Kar-wai's 2046, some movies seem more like a collection of a

director's greatest hits than the celluloid version of an original album. For Jean-Luc Godard, Pierrot le Fou was that film. But as Melissa Anderson notes in Time Out New York, it isn't just a replay of previous themes and techniques, but "a sneak peek at the dense cine-tracts that would follow."

Shot in 'Scope by Godard regular Raoul Coutard--who uses red as a re-

curring motif--and inspired by Lionel White's Obsession, Pierrot le Fou plays like Joseph H. Lewis's hopped-up Gun Crazy as only JLG could remake it.

Ferdinand (Jean-Paul Belmondo) is an aspiring novelist with a wealthy wife and two cute kids. One evening he hits the town with his spouse, while a woman named Marianne (Anna Karina) keeps an eye on the children. The hot babysitter happens to be Ferdinand's ex-girlfriend. And just like that, he

leaves his bourgeois life behind for a trip with her to the French Riviera.

The duo are without ducats, so they steal what they need. In short order, they set up shop in an abandoned villa. They've got books, a bird, a fox, a beautiful view, and each other. It should be Heaven on Earth. And it is. For a while...

First of all, there are Godard's iconic avatars: Belmondo and Karina--and their potent on-screen chemistry. Then there's the criminal element, which recalls Breathless (Belmondo), Band of Outsiders (Karina), and Weekend.

Then there are the musical interludes, which recall A Woman Is a Woman (Belmondo and Karina). Then there's the bathtub torture, which recalls Le Petit Soldat (Karina's first film with her future husband), and the tragic ending, which recalls Contempt. And that's the abridged edition. There are numerous allusions to the rest of Godard's filmography.

Like Two or Three Things I Know About Her, Tout Va Bien, and other 1960s and '70s works, Pierre Le Fou also serves as a condemnation of the Vietnam and Algerian Wars and of the Americanization of France. For instance, to make a little money, Ferdinand and Marianne put on a play for some happy-go-lucky US sailors. He portrays America, she portrays Vietnam. It's a gleefully offensive piece--Marianne mincing in yellowface--that leaves neither nation unscathed. From that point onward, the tone turns darker and darker until it all goes up in smoke.

So, Pierre Le Fou is beautiful and ugly. Violent and peaceful. Pretentious and primitive. Or, to quote Ferdinand (quoting Marianne), it's "tender and cruel...real and surreal...terrifying and funny...nocturnal and diurnal...usual and unusual." It's Godard in a nutshell--all for the price of one ticket.

***** ***** ***** ***** *****

Pierre Le Fou is not a film, but an attempt at film.

-- Jean-Luc Godard, Cahiers du Cinema (1965)

Pierrot le Fou opens at the Varsity Theater (4329 University Way NE in the U District) on Fri, 8/31. For more information, please click here or call 206-781-5755. Images from Janus Films and Senses of Cinema.

Friday, August 24, 2007

A Snapshot of Musical Taste at a Suburban New Jersey High School, Circa 1978-1981, or Was Billy Joel Cool?

On a Slog post last week, Dan Savage revealed his fondness for Billy Joel's "Only the Good Die Young", adding defensively that he didn't care whether Billy Joel is considered to be cool or not. Leaving aside the question of Joel's present coolness, it made me wonder, was Billy Joel cool back in the day? Well, that's a tricky question to answer. What's easier to answer is whether he was popular at my suburban New Jersey high school.

From 1977-1981, I attended Dwight Englewood, a prep school in Englewood, NJ, right across the river from NYC and a hop, skip and a jump from the George Washington Bridge. It was a small school, with about 100 kids per grade [alumni include Tony Bourdain, Mira Sorvino, and Brooke Shields!].

However, certain acts got quoted on a regular basis and, by looking at the heavy-hitters, one can get a good sense of what was "in." Therefore it's apparent that, in 1979 and 1980, Billy Joel was among the most quoted, an honor shared with the Rolling Stones, Bruce Springsteen, the Grateful Dead, Pink Floyd, and the Beatles. So, yes, in the wake of The Stranger, his first commercially and critically successful album, he was popular, but was he cool?

Well, like Blondie, you couldn't not hear him. Aside from "Movin' Out" and the title track, I never liked or bought The Stranger [or any of his records, for that matter], but was conversant with practically every song on the album, due to repeated radio exposure [plus my sister had the cassette, which she would play in her car]. So, everyone knew the songs and a few people really did dig him, but he was more like a part of the regional ambience than an artist one truly embraced.

Somebody who was cool, was Bruce Springsteen. I never dug him, but I understood why many of my classmates did. It's easy to see why. Like Joel he was part of the landscape, but in a way that seemed a million times more authentic. Now, one can have a huge argument over that, but what's inarguable is that Springsteen was from New Jersey and repeatedly referenced things in his songs about New Jersey, and gave a pretty good portrait of youthful yearning in New Jersey. So, maybe one can see why "Born to Run" struck a deeper chord than "Only the Good Die Young."

As Springsteen noted in his induction speech for Roy Orbison at the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, Orbison was one of those guys you felt most compelled to listen to in your bedroom at night. The same could easily be said of Springsteen. Listening to Springsteen, while lying in bed, you wanted to be him. Listening to Joel while driving on the Palisades Interstate Parkway, you were him. Springsteen represented your inchoate, teenage aspirations. Joel also represented your aspirations, if your aspirations were orchestra seats to Pippin and dinner at Mama Leone's.

Of more personal interest to me, than Joel or Springsteen, are the artists from that era, who are now universally thought to be cool, but weren't particularly popular back then. Despite being a few miles from downtown New York, most of my classmates never bothered to see the Ramones, let alone the Talking Heads, Television or Patti Smith, who was better known as the source of Gilda Radner's punk parody, Candy Slice, than as an actual artist. Needless to say, none of my classmates were fans of the Dictators, the Dead Boys, Suicide, the Contortions, or Teenage Jesus & the Jerks.

So, the kids at my school certainly preferred the big 70's acts but, interestingly, seemed to have liked them without any gender bias. Girls were as likely to quote Pink Floyd, Jethro Tull, and Yes as boys and boys were as likely to quote Carole King, Joni Mitchell, and James Taylor.

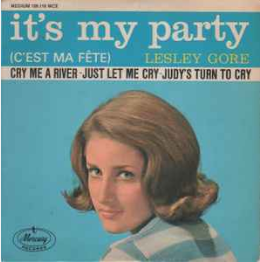

On a final note, I'd like to say that we at Dwight had our own pop royalty, the great girl-group artist Lesley Gore, class of '64, who recorded "It's My Party" while a student. Not only did she record a slew of great songs like "It's My Party," "Judy's Turn To Cry," and "Sunshine, Lollipops and Rainbows" [which always makes me smile when I hear it], but she's also a Jew and a lesbian. Now that, I think, rates a few clicks on the hip-o-meter.

1978

Cat Stevens 9

Beatles 4

Bob Dylan 4

Grateful Dead 3

Jackson Browne 3

James Taylor 3

Paul Simon 3

Steve Miller 3

Billy Joel 2

CSN 2

David Bowie 2

Elton John 2

Joni Mitchell 2

Led Zeppelin 2

Neil Young 2

Pink Floyd 2

Stevie Wonder 2

Yes 2

A Chorus Line 1

America 1

Barbra Streisand 1

Bruce Springsteen 1

Chicago 1

CSNY 1

David Crosby 1

Debby Boone 1

Jethro Tull 1

Jimmy Buffet 1

John Coltrane 1

Loudon Wainwright III 1

Pete Seeger 1

Rolling Stones 1

Seals & Crofts 1

Steely Dan 1

The Carpenters 1

The Who 1

Van Morrison 1

Fleetwod Mac 1

Billy Joel 5

Bruce Springsteen 5

Grateful Dead 5

Pink Floyd 5

Beatles 4

David Bowie 3

ELP 3

John Lennon 3

Led Zeppelin 3

Carole King 2

Cat Stevens 2

Chicago 2

Dan Fogelberg 2

James Taylor 2

Jethro Tull 2

Joni Mitchell 2

Kansas 2

Lynyrd Skynyrd 2

Yes 2

A Chorus Line 1

Al Jarreau 1

Al Stewart 1

Allman Brothers 1

America 1

Arlo Guthrie 1

Aztec Two Step 1

Barry Manilow 1

Carly Simon 1

CSN 1

CSNY 1

Frank Zappa 1

Gordon Lightfoot 1

Graham Central Station 1

Jackson Browne 1

Janis Joplin 1

Meatloaf 1

Milton Nasicmento 1

Neil Young 1

New Riders of The Purple Sage 1

Paul Simon 1

Ricky Nelson 1

Stanley Clarke 1

The Commodores 1

The Who 1

Warren Zevon 1

George Benson 1

Grateful Dead 13

Neil Young 6

Billy Joel 5

Joni Mitchell 4

Yes 4

Beatles 3

Bruce Springsteen 3

Pink Floyd 3

The Doors 3

Barry Manilow 2

Carole King 2

Chicago 2

CSNY 2

Dan Fogelberg 2

David Bowie 2

Genesis 2

Jefferson Airplane 2

Kenny Loggins 2

Rolling Stones 2

Argent 1

Beach Boys 1

Bob Dylan 1

Bread 1

Cat Stevens 1

Chuck Mangione 1

Devo 1

Donna Summer 1

ELP 1

Fleetwood Mac 1

Frank Zappa 1

George Benson 1

Graham Nash 1

Harry Chapin 1

Jackson Browne 1

Jethro Tull 1

Jim Croce 1

Marshall Tucker 1

Paul McCartney 1

Pippin 1

Rocky Horror Picture Show 1

Led Zeppelin 1

The Beatles 9

Grateful Dead 9

Bruce Springsteen 7

Pink Floyd 6

James Taylor 5

Lynyrd Skynyrd 5

Rolling Stones 5

Yes 5

John Lennon 4

The Who 4

CSN 3

Jim Croce 3

The Doors 3

Barbra Streisand 2

Barry Manilow 2

Billy Joel 2

David Bowie 2

Fame 2

Frank Sinatra 2

Jethro Tull 2

Jimi Hendrix 2

Joe Walsh 2

Led Zeppelin 2

Paul Simon 2

Pippin 2

Queen 2

Rocky Horror Picture Show 2

Rush 2

Allman Brothers 1

Art Garfunkel 1

Blondie 1

Blue Oyster Cult 1

Bob Dylan 1

Boston 1

Brian Eno 1

Cat Stevens 1

CSNY 1

Dan Fogelberg 1

Deep Purple 1

Elton John 1

Elvis Costello 1

Foghat 1

Genesis 1

Gordon Lightfoot 1

Hoyt Axton 1

Isley Brothers 1

Jackson Browne 1

Kenny Loggins 1

Little Feat 1

Molly Hatchet 1

Outlaws 1

Peabo Bryson 1

Ramones 1

Robbie Robertson 1

Rod Stewart 1

Rossington Collins Band 1

Seals & Crofts 1

Simon & Garfunkel 1

Stanley Clarke 1

Stevie Wonder 1

Strawbs 1

Street Scene 1

Styyx 1

Supertramp 1

Nancy Honeytree 1

Carole King 1

Doobie Brothers 1

Capt. Beefheart 1

Now I'm Home (to Stay): Roky Erickson Documentary You're Gonna Miss Me

YOU'RE GONNA MISS ME

(Keven McAlester, US, 2005, 35mm, 92 minutes)

I am not a member of the human race (not an earthling) and am in fact an alien from a planet other than earth.

--Roky's Declaration, June 13, 1975

Before watching You're Gonna Miss Me, I had just finished reading Eye Mind, Paul Drummond's exhaustively researched biography of Roky Erickson and the 13th Floor Elevators. So, I already knew about the psychedelic Texan and his mystical band of miscreants. Not that they're a new interest.

I'm not sure when I first heard the 13th Floor Elevators, but it was probably 20 years ago. Since then, I've been collecting their records (three full-lengths and a mess of bootlegs), following Roky's ups and downs, and writing about his work for a variety of venues.

That makes me an informed fan, though not exactly a scholar. Drummond and Keven McAlester, on the other hand, are experts on Erickson's strange and fascinating career. The book was eight years in the making, while the film took six (both began in 1999). Further, McAlester, a former Texan, is credited as one of the book's researchers, while Drummond, a Brit--like Julian Cope, who penned the foreword--appears in the film.To be an expert doesn't just necessitate an intimacy with Roky's recordings, but with Texas, hallucinogens, and mental illness. Texas, for instance, helped to make Roky the unique individual that he was--and remains. And in the form of its draconian drug laws, it conspired to destroy him (he did three years in a mental institute for possession). Like the book, the movie recounts Roky's rise, fall, and resurgence.

You may think you've heard this story before--and maybe you have--but that doesn't make it any less compelling. And the parallels with Be Here to Love Me: A Film about Townes Van Zandt and The Devil and Daniel Johnston are hard to deny: the three musicians all hail from the same state, two were subjected to shock treatment (Erickson and Van Zandt), and two were touched by madness (Erickson and Johnston).

And this isn't in the film, but not only did Erickson and Van Zandt co-habitate for a spell in 1968--they even dated the same woman--but Erickson and Johnston used to watch old horror movies together in the mid-1980s, inspiring Johnston's tribute, "I Met Roky Erickson" on the 1989 album with Jad Fair It's Spooky. It should also be noted that Richard Linklater associate Lee Daniel shot both You're Gonna Miss Me and Be Here to Love Me.

That said, McAlester's movie pivots on Roky's guardianship proceedings, and that certainly sets it apart from these other documentaries (the book covers the same territory, but not in as much depth). After making a splash with the Elevators in the 1960s, he pursued a solo career in the 1970s and 1980s, but years of heavy hallucinogenic use-over 300 acid trips-combined with pre-existing psychological problems, led to virtual incapacitation by the 1990s. The trial was arranged to transfer Roky's care from his eccentric mother, Evelyn, who doesn't believe in therapy-she prefers prayer-to Roky's younger brother, Sumner, who does.

Consequently, You're Gonna Miss Me revolves around Evelyn as much as it does Roky (his father, Roger, also puts in a brief appearance). While it's easy to sympathize with the sweet, if addled singer, his mother presents more of a challenge.

There's no doubt that Mrs. Erickson loves her oldest son, but doting on him to the exclusion of his siblings appears to have laid the groundwork for the trouble to come, since Roky never learned how to take care of himself. Instead, he bounced from woman to woman before returning to Evelyn--which seems to be the plan all along. Sumner, a classical musician based in Pennsylvania, turns out to be a bit of an odd duck, too, but one with a firmer grip on reality.By the end of the documentary, Roky is finally on the road to recovery, though I wish McAlester had been able to film for another year or two (fortunately, the DVD includes a postscript). As the book concludes, Roky has progressed beyond what the director was able to portray on screen.

Since its completion, he's started playing out again. First, a few gigs in Austin, where he returned after a sojourn in Pittsburgh, and now he's hitting locales that were beyond his grasp as a member of the Elevators (International Artists promised, but never provided any tour support).

As a taster for Roky's performance at this year's Bumbershoot, You're Gonna Miss Me gets the job done, even if his inimitable music takes a backseat to his mental state. For more on the former, Eye Mind delivers a greater share of the goods. The two complement each other well.

Sometimes people write something kind about what we did,

and I think, "Why not the Seeds, why not the 13th Floor Elevators?"

--Iggy Pop on the Stooges

You're Gonna Miss Me opens at the Northwest Film Forum on Fri., 8/24. The NWFF is located at 1515 12th Ave on Capitol Hill. Roky Erickson and the Explosions play the Mural Ampitheater on Mon., 9/3 (followed by fellow Texan Steve Earle). Eye Mind: the Saga of Roky Erickson and the 13th Floor Elevators, the Pioneers of Psychedelic Sound is set to be released in November. Images from Alternative Press, Amazon, and Michael Corcoran's Overserved (Evelyn and Roky 1991. Photo by Martha Grenon).

Monday, August 20, 2007

John Sayles on John Sayles: Part Six

***** ***** *****

On owning vs. leasing

We got the rights back to our first three films, which are Secaucus 7, The Brother from Another Planet, and Lianna. We're working on Matewan, but that's a tangled web. The company went out of business, and I think people were told, 'Well, we can't pay you, but we'll give you the rights to this.'

So, it's a big legal magilla, and we don't have much money to pull these things away from litigation or whatever. And something like Baby, It's You, if we can get the rights to a couple other films, what we might try to do is just say to Paramount, 'Will you lease us the right to put this in the package of three films?' Or something like that.

Nobody ever gives up their library anymore if the company is still in business. It's too--it's just not done. They don't want to starve, but they might be able to lease it. But even that--these corporations get more corporate and bigger, and they have more and more titles to deal with. They also start thinning out their staff, so all of a sudden, you have somebody who wasn't born when Baby, It's You was made, and they have a computer, and it has 500 titles on it, and they don't know what any of these movies are. Or if they do, they may not have seen it, and it just has a number next to it, or a 'Do not do this' thing. They don't have a mandate to be creative, so it's something that we bang our heads up against a lot.

[Killer of Sheep image]

On Killer of Sheep

It was a test case. When they used to do seminars for independent filmmakers: This is how not to do it. I think it was only able to play on PBS--and they have a different music licensing agreement than everybody else. Actually, they probably cleared the music rights. So, there are all kinds of movies that have wonderful music in them, and then the distributor finds out--we actually didn't secure the rights to that.

[The lack of music clearances resulted in a release delay of 30 years.]

On music rights

It used to be that you could go to--you know, Stax would have their own publishing and this, that, and the other. By about 1985-1987, those little companies started being bought up by the big companies, so now there's really, at the most, at least a half dozen companies that you have to deal with--VJ and Stax and all these little outfits that have their own publishing companies. And once again, it's just a computer list, and they set the numbers where everybody else sets them. And it's really hard to license music. So, the soundtrack for Baby, It's You, for instance, we'd never be able to get that together again. It would cost more than the movie now. Those are the breaks. I mean, Bruce Springsteen, who we didn't really know at that time, we said, 'Look we put these songs in the movie. Watch the movie.' And we sent a print over. 'If you hate it, we'll take them out.' And they liked the movie, and said, 'Here's what we'll do. We own half the rights, and we'll give half for a dollar or something like that.' We had to pay full price to CBS for the performance, but the publishing we got very cheap, and that's the one reason we were able to put Bruce songs in it. But that doesn't happen very often--as a matter of fact, most artists don't have that kind of control over their publishing. Performances usually belong to the record company. It's a rare artist who can control publishing.

[Sayles has directed three videos for Springsteen, including "Glory Days."]

[Phil Phillips image]

On Phil Phillips

So, when we were making Passion Fish, somebody said, 'See that extra over there. That's Phil Phillips, the guy who recorded 'Sea of Love.' And I think his name was Phillip Baptiste, or one of those Cajun names--his real name--but he recorded under Phil Phillips, and I got talking to him about [it]. 'So, it was great that your song, and they made a movie, and the song is played a dozen times in it,' and he said, 'You know, I didn't make any money on that. I made a couple cents as a performer.' He was one of the writers of the song, but by the time it got on the record label, it was so diluted by other people who had nothing to do with writing his song.

On the Rhythm and Blues Foundation

Ruth Brown started with Bonnie Raitt and a couple of other people this Rhythm and Blues Foundation, and some of them, because of that--people who actually created this music--got rediscovered when there were other media. When CDs came along, they weren't getting any of the money, and so they did some reparations--especially with Atlantic Records. I think they were the first label to say, 'Yeah, you've got a point.' Ahmet Ertegun, he was embarrassable. Some aren't embarrassable.

On film as an agent of change

I think movies are part of the conversation, and it can be a very important conversation. If you think of race relations in the United States, movies until about 1955 were part of the problem. If you watch old movies, racism was underlined and encouraged and reinforced by portrayals of black people, especially in movies. From about 1955 on, they started--very slowly--to be part of the solution. Sometimes--eventually--the most important thing was when it could be just a throwaway, and you had some black soldiers or some black ballplayers, and 'Nobody Knows the Trouble I've Seen' played on the soundtrack. You know, Denzel Washington is one of our big action heroes--we could do a lot worse, because he's a good actor. And he doesn't have to be in a movie that's only about black people.

[My tape ended as Sayles was about to say something about Inside Man.]

Reminder: John Sayles will be at SIFF Cinema on Sat., 9/1, at 12pm as part of Bumbershoot's 1 Reel Film Festival. Afterwards, the Honeydripper All-Stars play the Starbucks Stage at 3:15pm. For more information, please click here. As for the movie, Honeydripper is set to be released in 2008 after its premiere at this year's Toronto International Film Festival. For more on the writer/director, Sayles on Sayles is the title of the interview compendium from which these posts take their name.

***** ***** ***** ***** ***** *****

Images from Senses of Cinema, Google Images, and Wikipedia.

Sunday, August 19, 2007

John Sayles on John Sayles: Part Five

***** ***** *****

On John Huston

My idea of getting into the movie business--I always felt like there are two ways in--one way is to write your way in. That was the John Huston model, where you write a couple of things, and they do well, and then you keep bugging them about letting you direct, and they let you do it. The other was the Stanley Kubrick model, where you just go and make your own movie, and hope it gets a little bit of attention, and then keep bugging them, and say, 'Well, here's a movie that I made. Can you give me some money to make another one?' And so I started down the John Huston one, and it looked like it was gonna take forever, and so I hopped over to the Stanley Kubrick one, and got a theatrical release--which I did not expect--with my first film.

We shot Secaucus Seven in 16mm, and in TV ratio. I thought I might be able to get it on PBS or something, like Killer of Sheep when it first came out. And then, of course, when we got a theatrical, I had to do some up and down pan and scan, top and bottom pan and scan. There are some really awful compositions-where the ceiling is down on people's foreheads or up on their chins--because we had to make it in the Academy format to show it, instead of the square TV format we shot it in. So, both of those--I would say The Treasure of the Sierra Madre is probably my favorite film ever.

[Huston image]

On Huston's final years

Huston did a lot of literary adaptations. I've really never done those, but I always liked the feeling in his movies. There was a nice sensitivity to character, but the action was good, as well. And a nice sense of place. He didn't have the financing to do the big things anymore, and when he did, they were things like Annie, which he didn't have his heart in. I just did a little part in a movie Bertrand Tavernier is making, and Michael Fitzgerald is the producer. He produced The Dead, Wiseblood--a lot of Huston's last things. I think for Huston it was, 'If I'm interested in a subject, it's gonna be a good movie.' Sometimes he lost interest halfway through, or never was that interested, but needed to make the money, because he had five or however many things he wanted to make. His best stuff is the stuff he was interested in, and in the later years, he couldn't get financing the normal way, so they became independent productions.

On Fat City

I had always wanted to work with Stacy [Keach], and I got to talk to him a little bit about shooting that movie when we were making Honeydripper. He said there were some situations, like when they were picking onions in the field, that were shot pretty much documentary. They got out with a bunch of cameras, and he [Huston] said, 'Okay, Stacy, you're gonna pick onions this morning--better get yourself on the bus.' You saw the real pickers once they got out there. I don't know if he got paid for his picking.

On the author of The Treasure of the Sierra Madre

I'm a big fan of B. Traven. I've read most of his books, and he's one of these guys who tell great stories, even though he's not an especially good writer. Of course, he was writing in German, which was then translated into Spanish, which was then translated into English. He still wasn't a great prose stylist, but the stories are so good. And part of it is that he was a really observant guy, and he couldn't go back to Germany, and he lived in Chiapas, where no white people live. He probably was this guy who was Minister of Culture in Rosa Luxembourg's cabinet in Germany, and the day when the Nazis started killing all those people, he escaped. And it sounds like he may have literally had a dead man on the other side of his handcuffs, and eventually cut the guy's hand off or something to get away.

His father was a Chicago millionaire, and his mother was a German opera singer, and she hated him, and said, 'I'll support you as long as you never mention that asshole's name again.' He spoke some English growing up, and then he got out of the country by, I think, stowing away, and becoming a sailor on a steamer, and basically was a stateless person for awhile until he jumped ship in Mexico, and then was just paranoid for another 15 years or so. I mean, the Nazis could have come and killed him the way that Stalinists killed Trotsky. So, he changed his name. That story about him showing up, pretending to be the lawyer for B. Traven [in Huston's An Open Book] is probably true. Who got to be good buddies with him is Buñuel, so he has some stories about him, and he was always--even with his friends--his story changed every time you talked to him. Huston was a heavy drinker, and had a sense of humor and was a big practical joker, and B. Traven was a very non-ironic guy--they didn't exactly hang out at the bar together.

[There are allusions to Sierra Madre in The Brother From Another Planet, Men with Guns, and Silver City--the latter starring John's son, Danny.]

On adaptations

Actually, Honeydripper is based on a short story. It's based on a story in my last collection, which is called Dillinger in Hollywood. It came out about two years ago, and there's a story called 'Keeping Time,' about a 40-year-old drummer in a 20-year-old band, who runs into this old man, who tells them a story. The story he tells has something to do with the plot. It's just like Matewan came out of about a four-page section of Union Dues, which is a 500-page novel. So, it's often not a whole story, it may just be a story that one character tells that gets to be the germ of an idea.

[Baby, It's You image]

On Baby, It's You

As for Baby It's You, I don't know [when it will appear on DVD]. It belongs to Paramount. When we made it, by the time we got through the editing, the studio didn't like me or the film, and kind of released it, and said they were going to secure the video rights for the music--which is separate from the theatrical rights--and told Griffin Dunne, one of the producers, they were going to do that, so he didn't have to bother. And then they didn't, so it couldn't be shown on TV or video for a little while, and finally when the regime changed, and went over to Disney, the guy who was in charge was able to revive it, and we only had to change a couple of songs, because they'd gotten more expensive in the time in between. So, finally it could be on, like, Showtime, but it's just not high on their list to put out on DVD. It's up to them. They may be thinking, 'I don't think we'll make any money on this,' and it will cost us $100,000 on music rights, or maybe they don't even have the music rights. And it's just not a high priority. Unless it's considered some kind of classic film, like, you know, Animal House, they don't put everything out on DVD. It does cost them some money, and they have to do some publicity for it. It's like in publishing. If there's not a huge upside--if they can't make a little money--it's like, don't bother.

[Baby, It's You was based on a novel by Amy Robinson, who produced After Hours, which stars Dunne and Rosanna Arquette, who appears in Baby.]

Next: On owning vs. leasing, music rights, and film as an agent of change

***** ***** ***** ***** ***** ***** ***** *****

Images from Chlotrudis Society for Independent Film

and They Shoot Pictures, Don't They?

Saturday, August 18, 2007

John Sayles on John Sayles: Part Four

John Sayles on Black Snake Moan, Will Oldham,

Limbo, and Robert Altman (click here for part three)

On Black Snake Moan

We live up in the boondocks, and it just didn't play near us, so I'm afraid I'm going to have to wait for it to be available on video. We were invited to the premiere, and we were out of state, so we couldn't go to it, and that was our chance. I know those guys a little bit. I met them after they did the first one, their first Memphis movie--Hustle and Flow. They were describing the movie, and I said, 'Oh, so you're making [Walter Mosley's] RL's Dream, and they said, 'Wait--what's that?,' and then they got very nervous, and they said, 'Oh God, we've got to go read that.'

Hopefully, they were a bit better about it--because it is a different story--but it does have that same thing of this blues guy and this really disturbed white girl. They had just never heard of this thing, because it wasn't one of his 'color' books, like Devil with a Blue Dress or something like that. But, you know, they knew it was going to be a controversial movie. They were feeling like, 'Either we're gonna hit a home run with this or we're in big trouble...'

[Black Snake Moan was 2007's other big blues film. Great soundtrack.]

[Will Oldham image]

On Will Oldham

He was just playing with a guitar at the time, but he wasn't really recording anything, so I never heard him sing. When we made Matewan--we were looking for--Will was, I think, 14 when we cast him. He had done a couple of plays. He was from Louisville, Kentucky. There's a really good theater festival down there, and so he had done a couple things at that festival when they needed a kid. We heard about him, and he came up, and he was good, and he already had the accent--or could only thicken his slightly--and we were in business.

But while we were working with him, we knew that he was ambivalent about going to college, and he and his brother played guitar, and had bands together and stuff like that. So I wasn't really surprised when I heard that he'd started playing music. I was a little surprised that his voice never changed. It sounds like it's halfway between Leonard Cohen and Jimmy Stewart. A lot of it's such kind of intense personal stuff, really kind of nice and moody. And all the children of our friends say, 'Oh, you know Will Oldham!' They're really impressed by that. When we shot a movie in Denver [Silver City], we just missed Will. He was opening for Björk, and he was gone a week before we got there. We thought that was a good pairing.

On Limbo

We're the last idiots in the world who would actually shoot in Alaska. Basically, we were able to do it, because it was a studio-financed movie, and they gave us nine million dollars. We only spent eight, because we had a million dollars in contingency for terrible weather, and we were shooting in Juneau, where they get fourteen feet of rain a year. The thing that happened for us is that it did not rain for two weeks to the day before we started shooting, which meant that our carpenters and our painters could do all their work, and the paint would dry, and they didn't have to work in the rain, and we didn't get behind on any of that. And then, the first day, we were shooting a wedding scene, and what I know is that in Juneau, if you have an outdoor wedding and it rains-you get wet. And it's beautiful. It's kind of like Seattle; it's not usually [a] very hard rain. And you have a tent if you want to get out of the rain for awhile, and then it stops and it starts and whatever.

[Limbo image]

David Strathairn in Limbo

We didn't miss a day of shooting, so we ended up coming in a million under budget. They said, 'Oh really, send it back--quick.' Usually, it's Canada [doubling for Alaska] because the light is good and all that, and finally it was this thing of, it just seemed cheesy of us to do. If we could afford it, we could afford it. Juneau has a real character to it, and I wanted to use a lot of that, and there really isn't a Canadian city on the coast with that kind of character, and we could live in a city with an airport, and just ride to the end of the road 40 miles away, and portage a quarter of a mile, and we were in the wilderness. We had to give the crew the bear lecture, and all that kind of stuff. It was a long way to get out into the boondocks; they're all around you in Juneau.

On Robert Altman

In the case of Robert Altman, a lot of the inspiration for why Secaucus Seven was what it was came from his Nashville. I had acted and directed in theater, I had written fiction and for movies, and I had $40,000, and we wanted to make a movie. I knew a lot of good actors, and what can you do well with $40,000? What kind of story could I tell? And I realized, well, all the actors I know are about 30 years old. They're good actors, and they're not [in the] actor's guild yet, so I can pay them less than scale, and I realized with that much money and that little time, and a crew who hadn't shot a feature before, I'm not going to be able to move the camera around much, if at all. How am I going to get out of this thing where I don't have any motion? And one of the things that had just come out was Altman's Nashville, and you realize with parallel plots, there was always a reason to cut--[to] come back to a conversation or whatever--and that that would, in the editing room, give me a lot of leeway to put rhythm into the film that I couldn't put there with a camera.

We did exactly one tracking shot in all of Secaucus Seven. It was the first shot of the first day, and it took so long that, [with] the inexperienced crew we had, I realized, 'Forget it--put the track away.' We did handheld later on for some of the sports things, but that was pretty much it for moving the camera. So, that was very useful, that way of having these parallel stories and building the rhythm later on in the editing room, I didn't cut many scenes out; he cut quite a bit out of Nashville. [Later] he got bumped out of Hollywood, even though his movies were doing okay. He was never a big fan of them, and they kind of returned the favor. And he did the movies in Europe, and the Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean movie; he did Streamers.

He just [decided]--'Okay, if this is what I got to work with, this is what I got to work with.' And he did the best that he could. I think he also had to come up the hard way, because he had made industrial films, and then he became a TV guy, and [was in] that yoke for a long time, and although he had fun, he really didn't like the process of just cranking out Westerns, or whatever he was making for TV, so when finally he got a chance to direct, he just said, 'Look, I'm the director. Go away.' He wasn't as self-destructive as Sam Peckinpah, but he was certainly as independent-minded. I think the only one where he really didn't get everything he wanted was McCabe and Mrs. Miller, and that was more because Warren Beatty had his own ideas, and he was the power in it, rather than the studio telling him what to do. I think that movie was a great hybrid between a totally anarchic spirit and two movie stars, who did some of their best work in that format.

Next: On John Huston, B. Traven, adaptations, and Baby, It's You

***** ***** ***** ***** ***** ***** ***** ***** *****

Images from Senses of Cinema, Mes Nuits, and The John Sayles Stock Company.

Thursday, August 16, 2007

John Sayles on John Sayles: Part Three

John Sayles on advertising, distribution, YouTube, and the

UCLA Film & Television Archives (click here for part two)

*****

On advertising

Unfortunately, what's happened with independent filmmaking in the last 10 years is it's gotten more like mainstream filmmaking in that if your first weekend is not platinum, you disappear. We make movies very low-budget for as ambitious as they are. For instance, Honeydripper is about a five-million-dollar movie. We only had, with that, five weeks to shoot it, so it was very, very tight. But to make five million dollars back, you can't just play two weeks everywhere. You have to hang in the theaters a little bit longer, or you have to really use that theatrical opening as a kind of loss leader or something you break even on, like advertising, or other revenue.

Now the other revenue becomes problematic if everybody is going to go to their friend--you know, ten people are going to go to their friend and copy it from them, instead of buying it on DVD. So, I hope there's still a window for us to get people to either go to a theater or buy a DVD, or sell the rights to the movie or whatever.

[Return of the Secaucus 7 image]

Featuring Sayles, Strathairn, and NYPD Blue's Gordon Clapp

On distribution

However, we're basically not quite self-distributing this movie, but we didn't have a distributor, and we still don't have a distributor. You know, it's what we can afford. I mean, advertising has gotten so expensive that only the big studios can afford it. I'm still a screenwriter-for hire, and one studio just put out a fatwa saying: no dramas, no period movies. That's like a whole studio. They're interested in dopey comedies or big Spiderman kinds of movies. It's what they know they can sell; and that they know they can sell when they know they have to spend 20 million or more advertising it on television, because that's the way they do things. Even when they do a platform release, they're still buying television in those markets that they platform in, and it's really more expensive than we can handle. I mean, we basically spent all our money to make the movie, and we had almost none left for advertising.

On his first distributor

I had hitchhiked across the States, but I had never gotten as high as Seattle, so it's the first time I got up to the Northwest [when Specialty Films picked up Return of the Secaucus 7]. There was a guy named Randy Findley who owned the Seven Gables and the Varsity--six or seven of the best theaters--and he had done a little distribution.

He had distributed The Man Who Skied Down Everest, and a French movie that did very well. He bought our film partly because he knew he could make money in Seattle with it in his theaters, and then he sub-contracted a guy named Barinholtz, who invented the midnight movie with Eraserhead. He did most of the work east of the Mississippi, and Randy did most of the work west of the Mississippi. They were good guys. They really had a seat-of-the-pants, grass roots way of selling the movie.

So, we came to Seattle a couple of times and did publicity--in Portland, as well--and [we've] come back there to visit friends, and have fun since then. We've been to the Seattle International Film Festival several times. Randy ran those theaters for six or seven more years. Then he started a lawsuit against the two major theater chains in town--and studios. He had the best theaters, he would offer more money, but they still wouldn't give him a mainstream picture, so he ended up selling his theaters in the lawsuit to the new people who owned them. All the studios finally settled, except for one, and they lost triple damages. It was obvious they were doing some kind of secret bidding, under-the-table thing, and freezing him out.

On Seattle theaters

Seattle was the place--not only Starbucks started there, but Elliot Bay, where you can sit and read--but also the concept of an independent movie theater being a place where you like to go. You go to see what's there, and then it has some personality, and it doesn't look like every other one, and you can get coffee and a brownie or something--instead of just popcorn--and there are good seats. And Randy really sort of started that, and other people started copying it around the country.

So, it was a nice introduction when we were all trying to invent this independent film thing. He was a good guy to have hooked up with, and Seattle--at that time anyway, I don't know if it's still true--had the highest per capita movie-going and book-reading in the country. Probably because of the rain. And it's still true if you have a sunny weekend, you're dead. When your movie opens in Seattle, if it's beautiful and vibrant, it's like, 'Why go to a movie?' It's beautiful there when it doesn't rain.

[Matewan image]

Chris Cooper in Matewan

On the UCLA Film and Television Archives

First of all, UCLA's doing great work. It doesn't have to be an ancient film. It doesn't have to be a silent film or something from the 1930s to need restoration. And so a lot of... And so, out of my first 10 films, probably eight of those distributors are out of business, and so when we try to get the rights back or we try to get a print or whatever, things disappear. One reel of The Brother from Another Planet had disappeared, and we luckily had an intermediate something that we were able to find somewhere and make a new negative of. UCLA has helped doing a lot of that. Some film stocks don't exist anymore, so when we printed Matewan, which we re-did on our own, because we don't have the rights back, but we wanted to preserve it, even if the people who own it didn't. We had to print it on Fuji, because the Kodak stock it was printed on doesn't exist anymore. So there's a lot that goes into it.

On YouTube

What I would hope is that--the problem for everybody is how to get money out of this thing. It's great to get word-of-mouth going. It's great for publicity, in that you don't have to pay very much. It's just: is there any form that people will pay to see your thing? Movies have not gotten quite as downloadable as records have. For instance, not enough people are buying CDs. They're sharing them, downloading them, buying them a song at a time--not buying a whole album--or whatever.

Maybe in 15 years, everybody will be getting their movies in a different way. So, right now, it's good to have these things, and who you're reaching with them are the most movie-mad audiences, who are actively going to sites to look for what's coming out. It's not the biggest audience, but it is an important audience. I think for people just starting out, it's great. Unfortunately, for a while there was this phenomenon where even if you got your first movie into Sundance, if it didn't get a huge release or didn't do well on its release, that was it for you as a filmmaker.

There was no failing, there was no apprenticeship, and so now, I think, there are people who can-compared to me--who have made three or four movies on hi-def video. None of them cost more than a million dollars, but they got that experience, and you hope they don't get disheartened, and at least they have some--even if it only plays on YouTube or is downloadable for 50 cents--audience for it. You know, sometimes it's a little bit like going home and playing your violin and opening your case and hoping people put dollar bills in it, but people do okay doing that.

Next: On Black Snake Moan, Will Oldham, Limbo, and Robert Altman

****** ***** ***** ***** ***** ***** ***** *****

Images from NNDB, FRAMEONLINE, and The Stop Button.

John Sayles on John Sayles: Part Two

John Sayles on Ruth Brown, Keb Mo, Danny Glover,

and Guillermo Del Toro (click here for part one)

*****

On Ruth Brown

We hired Ruth to play a character named Bertha Mae Spivey in the movie [Honeydripper], somebody who sings in this club that Danny Glover's character owns. The idea is that it's as if Ma Rainey or Bessie Smith has retired to this little town, and comes in every once in awhile because she loves performing, and sings what is basically 1920s blues in a 1950s club, but there are not many people coming in to see her, even though she's still good at what she does. So, we did a pre-record with Ruth to figure out what the tempo would be, to give her some practice, to figure out what key she was the most comfortable in, and to record the piano because Danny Glover doesn't actually play, so when she performed it she would be performing live on film, but she would have the piano track in her ear.

It was really the last recording session Ruth did, and she was in very good spirits, very healthy. We had met her, and asked her to do it the year before, and she had been in such good health then, so we were really feeling good about her. And then as we were shooting the movie, she just called and said she had to have this surgery that was not supposed to be major, and I'm afraid it's one of those things when somebody goes into the hospital, gets an infection there, and that eventually killed her. She went into a coma, and very heroically, Mable John took the part with 10 days notice, and Mable had been on our list of people who might be able play it earlier, so we at least knew she was around, and still performing.

[Ruth Brown image]

Mable runs a ministry in Los Angeles, and sings in church every Sunday, and she used to run the Raelettes for Ray Charles, and fill in when one of the three was missing, so she's kind of an old trouper in that way, and she's one of the people touring with our Honeydripper Band that we've been doing these blues festivals with.

Click here for Sayles' tribute to Ruth Brown

On the Honeydripper All-Star Band

I'm going to be showing clips from the film. It's actually going to have its premiere at the Toronto Film Festival in September. So, I'm going to talk a little as part of Bumbershoot. The Honeydripper Band has turned out to be just terrific. I don't play an instrument. I've written some songs in the movie and some of my past movies, but I don't read music. I make up songs, and other people make them musical, but I'm amazed that we got these musicians, most of whom had never met before.

Our piano player, Henderson Huggins, is a blind guy from Tuscaloosa, who plays Danny Glover's hands in the movie, so he actually just mimed on a piano with no workings inside of it to pre-recorded piano. He shows up. And then Eddie Shaw, who plays a character in the film and is a saxophone player--he used to play with Howlin' Wolf-he brought a drummer and a bass player, and Mable brought her son, who's a bass player, and then Gary Clark Jr. Basically, we had a two-hour rehearsal, and the next day they were on a stage at the Chicago Blues Festival, and they sounded terrific. They just figured out about an hour and a half set, and went out and did it. It's just that thing that good musicians can do. And there are five of them that sing, so it's an unusual ensemble in that way. There's a real change of pace. Some are songs performed in the movie, and some are songs that each of them brings from,AeP Mable had a hit--she was actually the first artist on Tamla--she had a hit with Stax in the 1960s called "Your Good Thing Is About to End," and she does that. Eddie does some of the stuff he does with his group the Wolfmen, who are all veterans of Howlin' Wolf's group, and Gary Clark has some of his own songs, so it's a really nice,AeP It's been fun to listen to them. We did the Chicago Festival, and we did the River to River Festival in New York City, and then it's going to be in Long Beach, I think. And then up at Bumbershoot, and then a couple of other places--maybe Toronto. If we get the guys enough notice, we can usually get them all together. It's just a matter of--we don't have much money. If we can get sponsorship from somebody in the festival or some other group or whatever to help subsidize the airplane tickets and the hotels, we can usually get something together.

[Keb Mo image]

On Keb Mo

We're hoping that at one of these dates, if Keb Mo is around-because he's on his own tour-he can sit in for a bit. He has a terrific show. He came through Poughkeepsie, which is near us, and we went and saw him. He actually got sponsorship from a luggage company, because he had an album called Suitcase. So, he can carry a few more instruments and a little lighting and everything, so the first half of the show is acoustic and the second half is electric, and it's just incredible.

On Danny Glover

If there was going to be a long set-up [we talked politics]. Danny can do hours on whatever it is. We did talk about it. A lot of what we talked about is--Danny wants to make a movie about the Haitian Revolution, which I know something about, and now there's a timing... For awhile, it looked like he was going to make it in South Africa, because they have a film center, and it would be good employment for people there, and he knows Nelson Mandela, but it looks nothing--no part of South Africa look anything--like Haiti. And since he's also tight with Hugo Chavez, Chavez said, 'Oh, we'll subsidize this picture if you hire a lot of Venezuelans,' so he was thinking about making it there, but then, of course, all the Venezuelan filmmakers shouted out, 'Wait a minute--why don't you subsidize us?' It's very hard to do anything like that without stepping on somebody, so I don't know what he's going to do now, but it's fascinating history, and Danny knows a lot about it. He was very busy, so we got him right after doing two movies in a row. As a matter of fact, in the five weeks we had to shoot, we only had our lead for three and a half weeks. The scheduling was nightmarish. You know--'Can we actually have these guys in the same shot?', and that kind of thing. A couple of those movies are also [going to be] in Seattle, so we're hoping that one of the ones with a big-budget will fly him there instead of us. That's the kind of thing you have to think about. Danny's one of those actors who--he certainly is known for his Lethal Weapon films--but he's done a lot of really interesting, kind of very low-budget movies, just because it was a good part. He hasn't had a lead in something for a long time, and really, he's very good in this. And the other guy who really stands out is Charles Dutton. It's my favorite thing he's ever done on film.

[Guillermo del Toro image]

On Guillermo del Toro

I worked with Guillermo on that [Mimic]. There were a lot of writers on it, and I did several drafts. The funny thing about Charles [Dutton] in that is, I kept getting--not from Guillermo--but from Miramax, [with] each draft, they would say, 'Well, make the best friend a nerdy Jewish guy,' and then they'd say, 'Make the best friend a streetwise black guy.' And I'd say, 'Okay.' I kept changing them. When I saw the movie, they had chosen Charles Dutton, but half of his lines were still nerdy Jewish guy lines. He made them work. At the time Guillermo got to make that movie, the script was confetti. They put in a different color every time there's a change. I asked him--you know, Guiller-

mo's a big guy--'So, did they get their pound of flesh?' And he said, 'Well, more than that.' And he hasn't worked in that kind of movie where he didn't have control since. That's a movie that I think does some very good things, but I would say that it's not really a Guillermo movie. The end was never, I think, written on paper. It was one of those ends where it was by committee, and he wasn't invited to the meetings. In the end I wrote that was in the script for when, I think, he started shooting, the little autistic boy basically watches as his grandfather [gets] eaten, and it's like, 'Well, my friend, there are these bugs.' They didn't know who this guy was--or care. Guillermo has that kind of Buñuel-Catholic-perversity, and that was kind of missing from Mimic, so it had some of his style, but not much of his personality in it, but the bugs were great. He draws, and his notebooks look like Da Vinci's notebooks. It's incredible. Much of the design of the monsters comes from Guillermo's drawings. He's just great at that stuff. He started in make-up, and special effects in Mexican movies for years before he got to direct.

Next: On advertising, distribution, YouTube, and the UCLA Film & Television Archives

***** ***** ***** ***** ***** ***** ***** ***** ***** *****

Images from Metroactive Movies, All Music Guide, and Downtown Express.

Wednesday, August 15, 2007

Return of the Independent: John Sayles on John Sayles

My introduction to John Sayles dates back to the mid-1980s when I went on a VHS rental binge. Before that time, I'd been too busy with school to keep up with all the indepen-

dent filmmak-

ers emerging in the late-1970s, like Sayles and David Lynch. Plus, I'd been dividing my time between the art house-deprived communities of Anchorage, AK and Walla Walla, WA.

So, I started taking chances with the likes of Lynch's Eraserhead (1977) and Sayles's The Brother from Another Planet (1984). I had heard a bit about these cult classics, but not much. Mostly, I was intrigued by the titles, the cover art, and the offbeat subject matter.

As it turns out, The Brother from Another Planet, starring Joe Morton as a slave on the run from Men in Black played by Sayles and college buddy David Strathairn, wasn't his first feature. It was preceded by Return of the Secaucus 7 (1980) and Lianna (1983). That one-two punch secured Sayles's rep, and led to Baby, It's You (1983), but that experience soured him on the studio system. Sayles has been proudly independent ever since (and studio interference aside, Baby, It's You remains a nifty little picture).

Over 20 years later, I'm still following these filmmakers, which is ironic as Sayles and Lynch don't otherwise have much in common. They do occasionally take on work-for-hire--Sayles is currently attached to Jurassic Park IV--but they don't compromise when it comes to their own work. I have a great deal of respect for people who can figure out a way to do that, whether in filmmaking or any other field of endeavor.

Over 20 years later, I'm still following these filmmakers, which is ironic as Sayles and Lynch don't otherwise have much in common. They do occasionally take on work-for-hire--Sayles is currently attached to Jurassic Park IV--but they don't compromise when it comes to their own work. I have a great deal of respect for people who can figure out a way to do that, whether in filmmaking or any other field of endeavor.Last fall, I got to chat with David Lynch for 20 minutes. This summer, I got to chat with Sayles for three times that long. I came prepared--I've seen all 15 of his films, not counting the upcoming Honeydripper--but I'm not sure that it mattered.

Maybe it comes from being a novelist, but Sayles doesn't give short answers. Every response was rich with context. Consequently, the following represents unexpurgated Sayles. For more from the man, catch him at Bumbershoot presenting clips from Honeydripper, followed by a performance from the Honeydripper All-Stars.

[honeydripper]

On Honeydripper

The story is set in 1950 in a small town called Harmony, Alabama. Danny Glover plays a club owner [Tyrone Purvis] who's trying to keep it going with live music, and he's about to give it up, because he can't pay the rent, and nobody's coming in. The club has a jukebox, which is just kind of getting all

the young field hands, and the Korean War [has] started, and that was when the Armed Forces finally integrated combat soldiers, so there's an army base nearby. And it's really about the beginnings of what eventually would be called rock and roll. And it has a really nice cast. Charles S. Dutton is in it, and Mary Steenbergen, Stacy Keach, Keb Mo, the blues singer--a really, really nice cast.

On making a music film

You know, it's interesting, because music has been a really important part of the films I have made. I'd say this is the first one where music is the subject, or part of the plot. I'm always interested in evolution--in cultural evolution--and certainly in the United States. And one of the places where integration happened first was in music and sports. In Matewan there's a little bit of that, as well. There are people who are actually being separated from each other by mine guards, yet at least [they] can hear each other's music.

I'm interested in that evolution, and how that works, and how people make that choice to either move on, or stick with what they already know. It applies to a lot of areas in life, and in music, it's amazing how fast a new music will spread, and when that new music gets popular, there's always that choice that pre-existing musicians have to make: Am I gonna jump on this new thing, which I may or may not like? For the guys who are playing rhythm and blues and early jazz or big band, rock and roll was actually easier to play, and some of them didn't care for it very much, but to make a living they often...

Rhythm and blues vs. rock and roll

There was a label called Savoy Records in New Jersey, and these incredible Charlie Parker-kind of guys used to go and honk the saxophone on rhythm and blues songs for the take and then go play the jazz clubs for nothing at night--or very little, compared to the recording date where they were using a tenth of their talent--and they were good, but it wasn't their music. I'm always interested in that, in what that entails, or can you find something creative to do in this new medium. It happened for filmmakers--not just actors--who didn't make the cut when silent movies went to talkies. There were directors who just couldn't get a handle on this thing where they talked as well. It happens in fiction, and a lot of other places, and it happens in sports when they change the rules a little. There are people who get left behind, and other people really take advantage of it, and there are fans who just say, well, that's not baseball, or that's not football.

On the backbeat

On the other hand, some of the research and some of the stuff that you're hearing in Honeydripper--what they're calling rock and roll--had been around for a long time. One of the songs in the movie that you just hear coming from a liquor truck is "Move It on Over," which is a Hank Williams song. We actually shot the movie--part of it--in one of the towns that Williams grew up in. And if you listen to it, it's "Rock Around the Clock." And it's a comedy song, but its rhythm, its backbeat--everything--it's "Rock Around the Clock." And there are rhythm and blues songs, that you basically just say, 'Well, wait a minute, that's the basic rock and roll beat.' They just weren't calling it that then.

There was a drummer named Earl Palmer, who came out of New Orleans and was a tap dancer when he was a kid, and he eventually became the big session man in Los Angeles for early rock and roll, and he played on some of Fats Domino's records when he was still in New Orleans. He basically says, 'One day when I was still in New Orleans, Little Richard came in and he was singing so damn fast, I needed to put a backbeat to it just to keep track--just to not get lost--and he was off to the races.

The piano vs. the guitar

Life was speeding up. Another big thing that was happening that you see some in the movie... We found Gary Clark Jr., who plays this young guitarist [Sonny] who comes into town. He [Clark] is a guitar phenomenon from Austin, Texas. We met him the day he turned 21, and could play in the clubs without his mom being there, which was lucky for her--although she likes his music. He plays this guy, who--and he's the first person--they look in his guitar case, and there's a guitar in there, but it's got wires coming out of it, and there's no hole in it, which would have been very, very new anywhere, especially in rural Alabama. The idea is that he's somebody who's heard about this thing that has been made in a couple of places, and he's a guy who fixes radios and reads Popular Electronics, and he's made his own, which was kind of where it was at.

Basically, one of the subtexts of the movie is this battle that went on for awhile between the piano and the guitar--which was gonna be the lead instrument, and until the electric guitar--and truly, the solid body electric guitar and the amp that went with it--the guitar didn't have the volume to be the lead instrument. And then Chuck Berry came along, and everything he was playing was in a piano key, and in fact, it was basically boogie-woogie piano on a guitar. So, it was kind of a little battle between him and Jerry Lee Lewis, and Chuck Berry won, and the saxophone disappeared after a couple of years, and then the piano disappeared for awhile, and if they were around, they were in very, very subservient positions to the guitar for about 20 years. And some of it was just technology, and that happens as well in sports as well as in music. What do people do with that new technology? There's a long story Danny Glover tells about a black slave, who, when the master isn't looking, sits at that piano, and just thinks, 'Man, I could do some damage with this thing.' It's not part of his culture--the music is--so what can be done with it? What's that new thing when you join African music to the piano?

On 1950

Then there's this kind of Tampa Red--it was called hokum music--that the character of Bertha Mae [Spivey] sings and some old 1920s blues, and then Keb Mo does some traditional blues, and then there's rhythm and blues, and you can hear big band stuff still coming--1950 was a real crossroads for all this.

You had Perry Como next to big bands next to funky blues next to rhythm and blues, and then the beginnings of this electrified guitar stuff, so there was a lot going on, and it was somewhat regional still. Even though radio had homogenized things quite a bit, it took a while for local bands to start playing things.

[honeydripper]

Next: On Ruth Brown, Keb Mo, Danny Glover, and Guillermo Del Toro

*****

John Sayles will be at the McCaw Lecture Hall on Sat., 9/1, at 12pm. The Honeydripper All-Stars play the Starbucks Stage, AKA the Mural Ampitheater, at 3:15pm. For more information, please click here. Images from Identity Theory (Sayles portrait by Robert Birnbaum), HomeVideos.com, Filmmaker Magazine, and Emerging Pictures.

Friday, August 10, 2007

Kehr on Gainsbourg

"Come Dance With Me" was the first film of a young singer-songwriter, Serge Gainsbourg, who would gradually age into the position of France's foremost hipster, a combination of Burt Bacharach and Jack Nicholson. He's a reptilian heavy in "Come Dance" - the photographer behind the blackmail scene - but he has an insolent, punkish quality that makes him much more interesting than the squares whom Ms. Bardot's characters are generally, and inexplicably, drawn to.

As Kehr implies, it's not a very good film, but Gainsbourg has a couple of good scenes that steal the show. It's not so much that's he's insolent or punkish, which he is, but that he's so high-strung, he lacks any credibility as an effective blackmailer, let alone one who is supposed to operate with a modicum of stealth. He plays the character with such a fidgety, guilt-ridden demeanour, that you can't imagine him walking down the street without getting arrested. In any case, it's a fun little part in an otherwise innocuous film. So, for Gainsbourg fans, it's worth searching out.

In addition, the Bardot set includes /Ae Coeur Joie by Serge Bourguignon, a director I am completely unfamiliar with. Jane Birkin tells the story that, when she first met Gainsbourg, she had no idea who he was and referred to him as Serge Bourguignon. I always assumed this was some kind of diss on his boozy persona, conflating his name with the traditional French recipe of beef stewed in red wine but, if there actually was a Serge Bourguignon, maybe she just confused the two Serges. In any case, I now have a new Bardot film and a new Serge to explore. I also have an utter craving for beef bourguignon, but the weather's still a little too warm for that.

Thursday, August 9, 2007

An Account of His Disappearance: This Is Gary McFarland

(Kristian St. Clair, US, 2006, 71 mins.)

He was an overdose of style.

-- Guitarist Joe Beck

*****

First things first. I know filmmaker Kristian St. Clair. I don't know him from

his directing, but because I briefly worked in the same department at Amazon

(DVD and Video) and, for a year or so, we belonged to the same book club.

That doesn't mean I know him well, but full disclosure merits a mention.

Further, I've always admired his taste in books, music, and film (like me, he has a thing for 1960s-era Michael Caine). Back in the day, I knew he was working on a documentary, but I didn't know whether or not it would ever see the light of day.

When you work full-time, it's tough to complete a feature-let alone start one in the first place-but that's exactly what St. Clair has done, and This Is Gary McFarland premiered in Seattle, as a work"n-progress, at 2005's Earshot Jazz Festival. Then,

it had its official launch at last year's SIFF (it's played other festivals since). Unfortunately, I missed both screenings, so St. Clair offered to send me a copy.

This is Kristian St. Clair

Back in 2000, when I found out he was working on this film, I can't say I was all

that familiar with his subject (at first, I thought he was referring to pianist Marian McPartland). If I didn't know anything about jazz, that might not seem significant, but I hosted KCMU's "Straight No Chaser" in the early-1990s. That said, I'm no expert, just a fan of the form, so I guess it isn't completely surprising that I wasn't intimately acquainted with vibraharpist/composer Gary McFarland (1933-1971), but

I figured if St. Clair was into the guy, he must've been a pretty interesting figure.

After watching This Is Gary McFarland, I'd have to agree that he was. This is a

lively effort, filled with useful information, and swinging sounds that could appeal

as much to general music lovers as to jazz aficionados. And that's the point, really. McFarland started out as a jazz musician, but later pursued a passion for pop,

hence St. Clair's tagline, "The jazz legend who should have been a pop star."

Just as tenor saxaphone player Stan Getz crossed over to the pop crowd with

1963's Getz/Gilberto, which spawned the classic "Girl from Ipanema," McFarland followed suit with 1964's Soft Samba, an easy listening affair that outraged the

jazz community. Fortunately, many forgave him when they realized he wasn't

trading one genre for another, and he continued to work in both idioms.

McFarland also had a certain savoir faire that impressed men and women alike.

(He married in 1963, and the wedding video reveals a rather...lustful couple.)

In photographs, he recalls RFK Jr. with a snappier dress sense-dig those mohair sweaters! And subjects attest to his charm and good humor. Nice guys, however, don't always make for the best cinematic subjects. McFarland didn't have a mean streak, but he does appear to have had a dark side. His wife mentions a history

of alcoholism, but this line of inquiry isn't explored in much depth. In any case,

he liked to drink, but that wasn't unusual for a jazz musician in the 1960s.

Nonetheless, McFarland didn't drink himself to death. Nor did he take his own

life. Instead, someone laced his drink with liquid methadone, and he suffered

a fatal heart attack. No one knows whether he was murdered or whether he was

the victim of a prank gone horribly wrong, although all agree that the methadone originated with Terry Southern associate Mason Hoffenberg (Candy), who was in

the same Greenwich Village bar that night. I recall that when he was part of our

book club, St. Clair recommended Raymond Chandler's The Long Goodbye and

James Ellroy's Black Dahlia. Suffice to say, the man can appreciate a good mystery, but-as with the death of Elizabeth Short-this one will probably remain unsolved.

On the whole, I like the way St. Clair keeps things humming along in the film-

and McFarland liked to hum on his bossa nova"nspired recordings, so that seems particularly apt-but I still would've liked more. By that, I mean more information, more stuff. I wish he could've dug deeper, but I suspect he went as far as he could.

Consequently, the documentary feels more like an introduction than a definitive biography, although that isn't necessarily a bad thing. Beforehand, I didn't know much about Gary McFarland. Now I do. I just don't feel like I understand what made him tick, although that can be difficult to pull off when your subject has been dead for over 35 years, and didn't leave behind a wealth of autobiographical material.

As an introduction, however, it serves its purpose, and serves it well. If St. Clair hadn't made this film, it might never have gotten made. Furthermore, when a director digs too deep, viewers can be left with little to discover on their own.

Instead, This Is Gary McFarland offers a primer for interested parties to go out and do some sleuthing of their own-to track down the records he made, to watch the films he scored, etc. They aren't all easy to find, but the musician wasn't a Nick Drake-type figure. He didn't produce only a handful of albums before his passing.

McFarland left his mark on scores of recordings by Gerry Mulligan, Anita O'Day, and other notables, let alone his own wide-ranging catalog, and the very existence of this film can only bring more attention to his efforts. For a first feature, it's remarkably accomplished, and I hope St. Clair gets the opportunity to make many more.

For more information, please visit the official website. To download MP3s, see

this section. The site also features record reviews and all of the pictures above (plus others). This is Gary McFarland isn't currently available on DVD, and no screenings are scheduled at present, but I'll update this post as soon as that changes.